Name Plates and Baggage Tags

This month, I’m going to share my collection of name plates and baggage tags that I’ve found while metal detecting. These are always fun to find because so many are lost to time when they’re thrown out with the motor or otherwise destroyed, making them pretty hard to find.

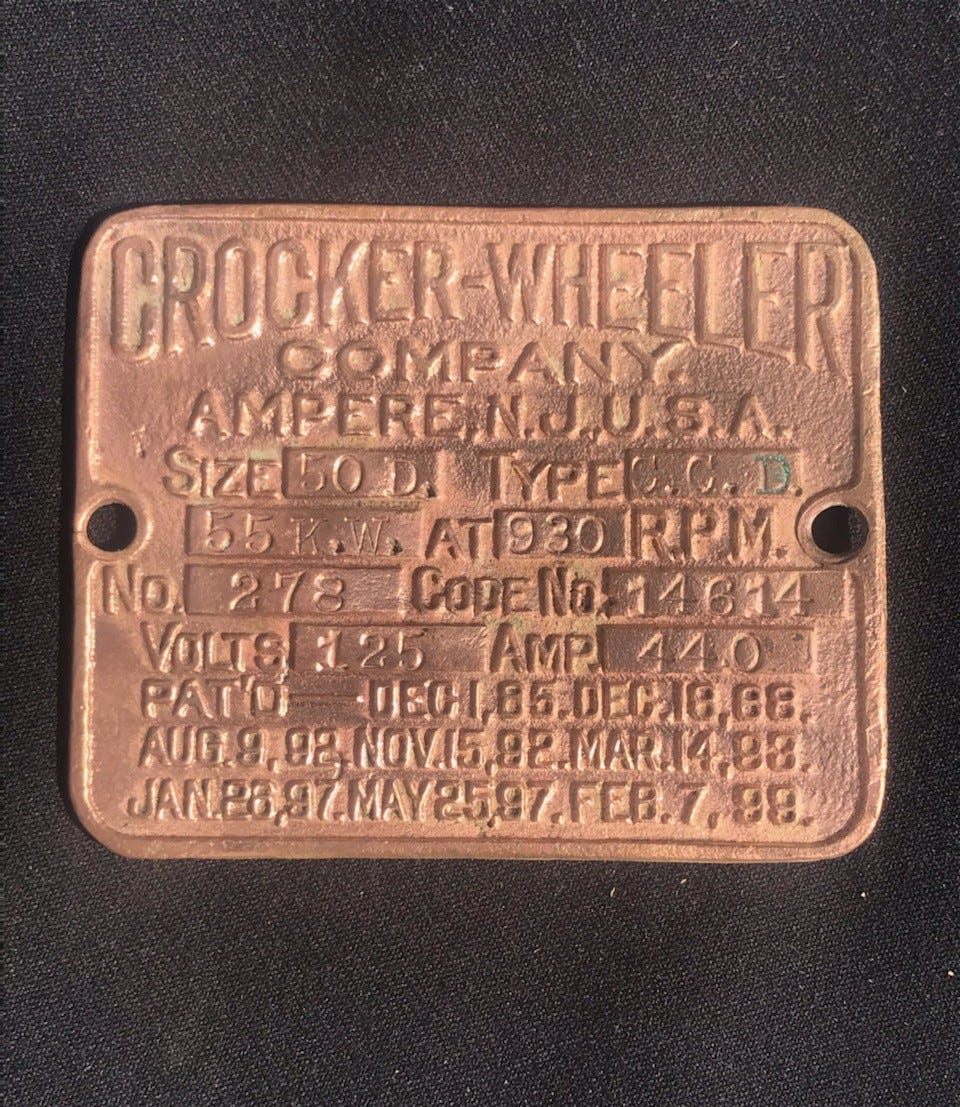

In 1888–89, electrical pioneers Francis Crocker and Schuyler Wheeler joined forces to found the Crocker-Wheeler Electric Motor Company, a firm that helped bring compact, reliable electric power into everyday life. Their motors were marketed for factories, small shops, offices, and homes, driving lathes, presses, and drills, and even running elevators, fans, and sewing machines. This particular name plate lists a number of patent dates, the first one being December 1, 1885, and the last being February 7, 1899.

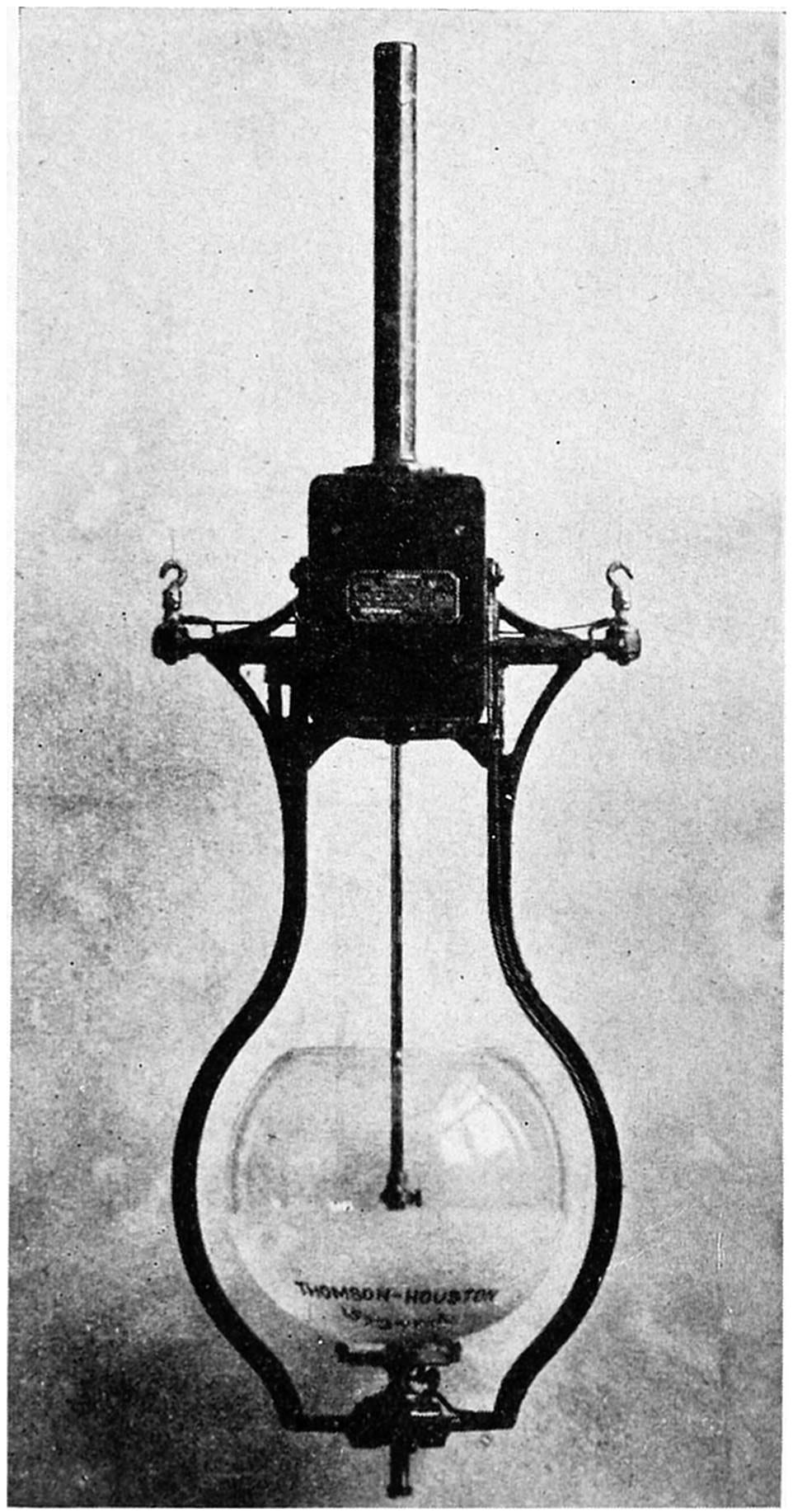

Arc lamp tag (Thomson–Rice / Thomson-Houston system)

This tag comes from an arc-lamp system developed by Elihu Thomson and Edwin W. Rice Jr. for the Thomson-Houston company, a major supplier of electric-lighting gear in the late 1800s. Patent dates are from February 21, 1882 to November 18, 1890. Rice managed Thomson-Houston’s factories while Thomson led R&D; both later helped form what became General Electric.

Carbon arc lamps make light by striking an electric arc between two carbon rods; the intense point source was ideal for street lighting, searchlights, and later, movie projectors. The technology spread quickly in the 1870s–1880s: by 1890, contemporary tallies put well over 130,000 arc lamps in service across the United States (some estimates run higher). Early film studios and theaters relied on carbon-arc projection for decades because nothing else was bright enough for big screens

Incandescent lamps (and, in cinemas, later xenon arcs) were quieter, safer, and easier to maintain, leading to their replacing carbon arc lamps by the turn of the century. Open carbon arcs had real drawbacks—intense UV output, sparks and heat that posed fire risks (especially with nitrate film), ozone and fumes that required good booth ventilation, and shock hazards from high currents. “Enclosed” arc designs in the mid-1890s extended carbon life but didn’t erase the safety issues, which is why codes and practices evolved to isolate, ventilate, and eventually replace them.

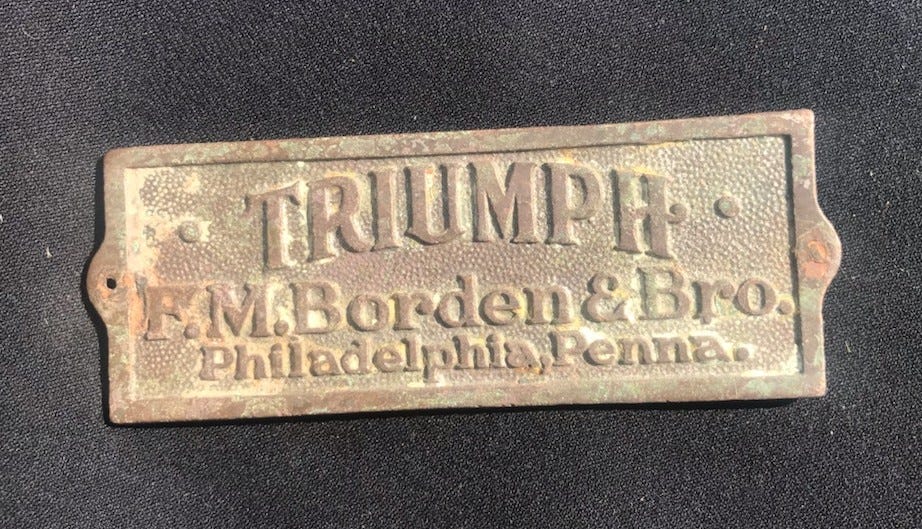

Borden and Brothers was a company in Philadelphia known for selling stoves and refrigerators in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Triumph is a model of stove. *Note: This is not the same Borden that is famous for Condensed Milk.

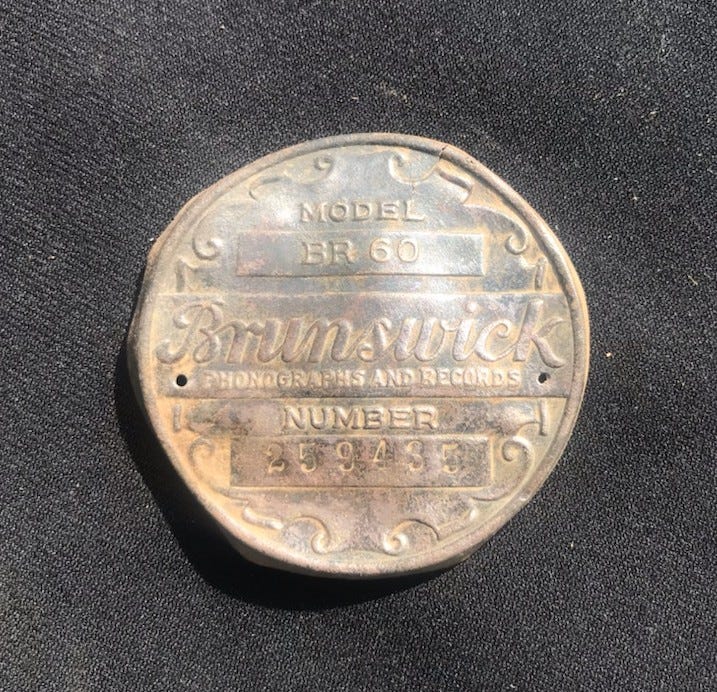

This plate came from a Brunswick BR-60 console made around 1924. It’s an early “all-in-one” with a phonograph for 78 rpm records and a built-in radio. Many BR-60s used Brunswick’s Ultona sound head, which could play several record types of the day, and were paired with a popular Radiola radio unit. Brunswick started building its own phonographs in 1916 as part of the Brunswick-Balke-Collender Company, which also launched the Brunswick record label soon after. (You’ll see “Brunswick-Balke-Collender” on many tags and plates from the period.)

Harleysville Insurance (Harleysville, PA)

Harleysville, in Montgomery County, about 32 miles northwest of Philadelphia, traces its roots to 1915 when local residents formed an association to protect against the new problem of automobile theft. The effort was formalized over the next few years, leading to Harleysville Mutual Casualty Company in 1922; in 1933 it merged with the Mutual Auto Theft Company as the business broadened beyond theft coverage. These brass “policy tags” were usually screwed to the car—most often the wooden dash, firewall (under the hood), or sometimes a license-plate frame/crossbar. Owners used small round-head screws (or rivets) through those holes to fasten the tag to a flat surface.

In 2012, Nationwide Mutual Insurance Company acquired Harleysville.

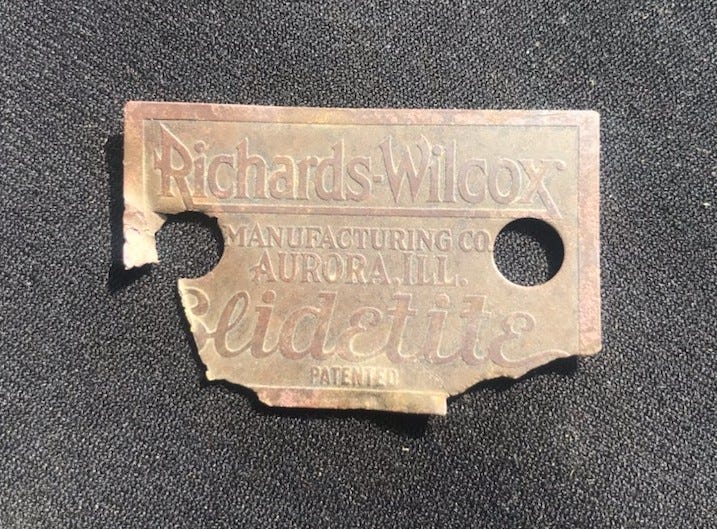

Founded in Aurora, IL, the Richards Wilcox firm traces its roots to 1880; over time Aurora makers Richards Mfg. Co. (active by 1903) and Wilcox Mfg. Co. merged in 1910 to form the Richards-Wilcox Manufacturing Company. This tag was more than likely attached to a garage door, which was one of Richards Wilcox’s specialties.

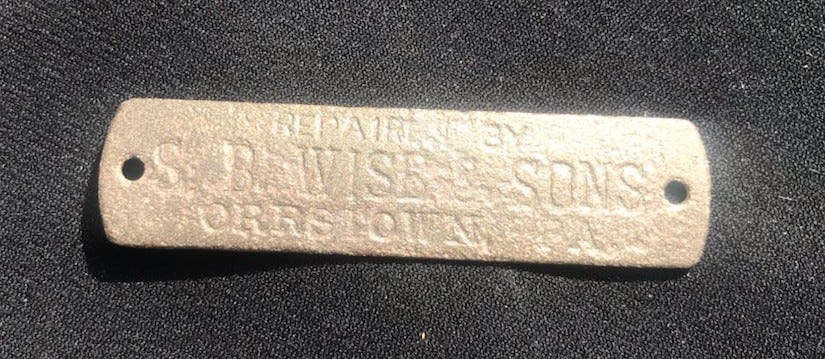

S. B. Wise (Orrstown, PA), carriage maker & repairer, late 1800s–early 1900s.

Founded by Samuel Beetem Wise, later S. B. Wise & Sons. The firm’s work is tied to the Orrstown Bank collection, which displays a restored Wise falling-top carriage—the same style depicted in the bank’s historic logo. This tag was apparently from someone’s carriage that needed repaired at one time, but was later discarded and left to rot.

Railroad baggage claim tags used a simple two-part system: one tag (the strap check) was fastened to the luggage with a leather strap, and the matching claim check was given to the passenger. The strap check typically showed the destination and a unique number so railroad staff could sort and track the bag, while the passenger’s check served as the receipt to reclaim it at arrival. Early tags were durable brass; often oval or round, with slots for a strap. As rail travel scaled up in the early 1900s, most lines shifted to paper/cardboard checks for speed, cost, and easier printing. This system helped prevent mix-ups, deter theft, and speed station baggage handling.

The Philadelphia and Reading Railroad opened in 1842. Through leasing, purchasing, and merging with smaller railroads, it extended its reach to Shippensburg, PA, where it connected to the Western Maryland Railroad. This particular tag reads “Hayes Grove,” which is a small village between Shippensburg and Mount Holly Springs.

Of all these finds, this one from the Cumberland Valley Railroad is my favorite because of the local history and the age. The Cumberland Valley Railroad (CVRR) was chartered by Pennsylvania in 1831 to link the Susquehanna River near Harrisburg with towns to the southwest. Service began in 1837, first to Carlisle and then Chambersburg, opening the valley to faster freight and passenger travel.

CVRR was an innovator: in 1839 it introduced the first U.S. sleeping car, the Chambersburg (soon followed by the Carlisle), on the run between Chambersburg and Harrisburg.

The line’s reach grew southward: by the late 19th century it connected Hagerstown, Maryland, and ultimately extended into Virginia, reaching Winchester in 1889. This made the CVRR a key north-south link between Pennsylvania and the Shenandoah Valley.

During the Civil War, the railroad was strategically vital for Union logistics and repeatedly targeted by Confederate raids; shops, depots, and bridges around Chambersburg were attacked during the Gettysburg Campaign.

The Pennsylvania Railroad (PRR) gained control over time and merged CVRR into its system in 1919, creating the PRR’s Cumberland Valley Division. As highways improved, local rail traffic waned; passenger service was gradually reduced in the mid-20th century.

The CVRR was a pioneering regional railroad; early to adopt comfort innovations like sleepers, crucial in wartime, and ultimately absorbed into the PRR as automobile and truck travel reshaped transportation in the valley.